Homelessness may be a complex issue but we know how to make a difference, heard delegates at a conference that brought together academics and experts by experience. DDN reports.

Read the full article in DDN Magazine

‘Outreach workers would try and contact me, but I couldn’t hear, they couldn’t get through. I was fretful and frightened.’ Kevin Dooley is now a recovery programme consultant, but at a conference on addressing complexity: homelessness and addiction’ he cast his mind back to a time when he was homeless, addicted to drugs and alcohol, and in and out of prison.

‘I would wake up when I was homeless and not know what time it was – I didn’t know the day or the month,’ he said. ‘I would open my eyes and see Boots the chemist through the gloom, and I’d know I could shoplift.’

When Dooley left prison, he ‘was on everything but roller skates’, but had no support, no crisis plan, no therapy, and was homeless. Vulnerable in every way, he found it impossible to ask for help.

‘Vulnerable people are being penalised rather than supported,’ he said. ‘To penetrate this, we need to understand the problem… Why do people get out of their heads every day? To become functional, to find a sense of wellbeing. Homelessness is not an intelligence deficiency. Addiction is not an intelligence deficiency.’

We needed to attempt a much deeper understanding, which would help to develop more reflective practice, he said. Relationships were important and sometimes all people needed was ‘a good listening to’. But it was essential to become fully informed about the effects of trauma in early life and realise that ‘the problem was there before the drug dealer came, before the first drink’.

‘It’s a growing problem that’s getting worse and that we need to do more to address,’ said conference chair, Prof Tony Moss. Each measure of homelessness had increased across England since 2010 and deaths of homeless people had increased by 24 per cent over five years.

When represented in the media, the problem was caused by drugs, alcohol, Siberian winds – but never by austerity. ‘The question really should be “why is this problem happening in the first place?”,’ he said. ‘It’s important not to perpetuate the myth that people are dying because of drugs and alcohol.’

Lack of compassion

Most deaths attributed to drug poisoning were ‘thoroughly preventable’, said Prof Alex Stevens, of the University of Kent. ‘The problem is not lack of evidence, but lack of compassion. It’s a class attempt to write people off and not think of them as fully human.’

Leading a report for the ACMD on how to reduce deaths in 2016, he had recommended opioid substitution therapy (OST), drug consumption rooms (DCRs), integrated services, and ‘putting naloxone everywhere’. Latest data from PHE showed that only 12 per cent of people were leaving prison with naloxone, when the odds of death from overdose were eight times higher without it.

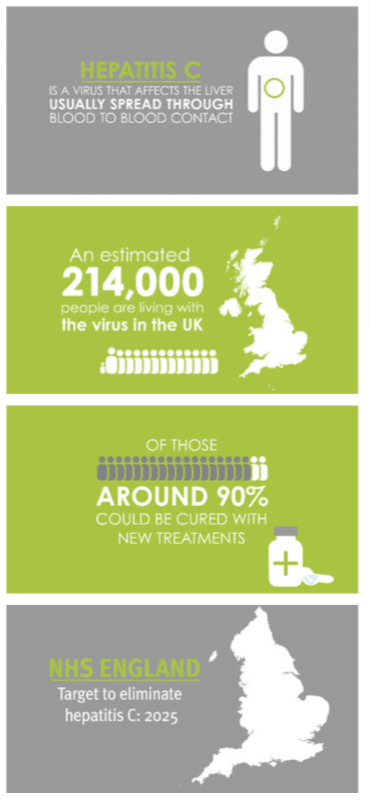

‘We should be getting people into treatment and keeping them there,’ he said, explaining that people were nearly twice as likely to die when they were out of OST. Treatment should also involve service integration and assertive outreach, linking drug and alcohol treatment to housing, mental health support, HIV and HCV testing, help with employment, relationships, diet and exercise, and smoking cessation.

There were many things that we could do and should be thinking about ‘rather than just getting people on a script’, he said, such as offering vaping pens to replace the ‘crappy roll-ups’ that caused lung disease.

With evidence being ignored on many initiatives that would have a positive impact, Stevens concluded that the main barriers in drug policy were ‘power and morality’; fiscal policies had redistributed wealth upwards and you were nine times more likely to have a drug-related death if you were from one of the poorest communities. We needed to change the narrative, he said, humanising people who use drugs as ‘people worthy of compassion and fully worthy of respect’.

There were many practical things that we could do to improve life for homeless people, the conference heard. In his opening address Prof Tony Moss said, ‘we’re not particularly good at working together’, so the event went on to share a wide range of expertise.

No help for smokers

Dr Lynne Dawkins of London South Bank University (LSBU) explained the strong link between homelessness and tobacco use and looked at opportunities for harm reduction.

Smoking killed around 200 people a day in England and was responsible for more than a quarter of cancer deaths – and with the average pack price almost £10, it was expensive.

‘You’d expect people on the lowest incomes to be the most sensitive to price changes, but that’s not what the evidence shows,’ said Dawkins. ‘Those who smoke can least afford it.’

While there was a slow but steady decline in smoking in the population as a whole, there were widening health inequalities in people who smoked. It was estimated that 77 per cent of homeless people smoked, which could exacerbate the onset of psychosis.

‘The desire to quit is no less in the homeless population, but attempts are often unaided,’ she said. ‘In some cases, smoking cessation is discouraged as it’s felt they can’t deal with it – that it’s “the only pleasure they have”.’

Evidence had shown e-cigarettes to be 95 per cent less harmful to health than smoking, eliminating the tar and the exposure to 4,000 chemicals, including 60 carcinogens. They gave much faster delivery of nicotine than patches, could replace the all-important hand-to-mouth activity, and didn’t feel like a ‘quit attempt’ to many that tried them. So why aren’t we considering e-cigs for the homeless, an extremely nicotine-dependent population, she asked.

Nothing to lose

Another problem that disproportionately affected homeless people was gambling, and Dr Steve Sharman of the University of East London who had looked at whether gambling was a cause or a consequence of homelessness. ‘Most gamblers have problems before becoming homeless, but also a smaller proportion took it up afterwards – so it’s more complex than we thought,’ he said.

He shared case studies which showed the gradual onset of a gambling habit. Dean’s gambling had started when he was 14 and used to go with his father to collect his mother from the bingo hall. Playing on the slot machines while they were waiting became the start of a habit that led to stealing from friends and family, spending all his wages, becoming homeless when his landlady evicted him for not paying the rent, and two suicide attempts.

Tom was abused from a young age and in care at ten, discovering drugs and alcohol as a way of escaping the negativity he was feeling. He and his girlfriend had a baby at 15, when his gambling career started with interactive tv games; before long he was spending their child benefit in the bookmaker’s, committing burglary, street robbery and violent crime to fund the habit, and became homeless after a spell in prison.

Using the information from personal stories, Sharman was developing a series of tools including a resource sheet with immediate tips and safeguarding measures (freely available at www.begambleaware.org). Fewer people were aware of treatment services for gambling than for drug problems, so the challenge was to find those in need of help, particularly if they were ‘lost’ to the system.

Body and mind

One of the other key areas for review was effective treatment for dual diagnosis, where poor mental (and physical) health overlapped with substance misuse – a situation all too common in homeless people. Using qualitative research, Dr Hannah Carver of the University of Stirling had looked at what could be effective for people in this situation.

As well as long-term, tailored treatment that looked at underlying conditions, it was found that peer support and compassionate non-judgemental staff were important to outcomes. The right environment and the right intervention needed to be paired with stability and structure, and opportunities to learn life skills. ‘Services should be facilitative and friendly, treating people “where they’re at”,’ she said.

Care pathways

Across every facet of healthcare there was evidence-based information that could go a long way to improving the lives of people experiencing homelessness. But as Dr Michelle Cornes of King’s College London demonstrated, the theory came to nothing if multi-professional teams did not work as a unit around the person needing help.

‘The picture is very fragmented,’ she said. ‘We often talk of the need to get physical health better before mental health.’ But pathway teams, including nurses, GPs, housing workers, social workers and occupational therapists, needed to be part of the care team – demonstrated in the case of hospital discharge. The recuperation, rehab, resettlement and recovery were all part of intermediate care that ‘has been shown to give enormous benefits’, she said. She introduced Darren and Jo, experts by experience, who explained what happens when the care pathway breaks down.

Jo had been discharged from hospital to the street with a gutter frame to aid her walking. She had no money and a 0.6 mile walk to her usual sleep site. She then had to walk a total of 6.8 miles on her walking frame over the next two days – to the GP surgery, the day centre to see if there was an emergency bed for the night (there wasn’t one with disabled access), back to the sleep site, to the ‘appointed’ chemist to pick up methadone, back to the GP for assessment, back to the chemist, back to the GP, until finally a taxi was arranged to take her to an intermediate care bed in a local hostel.

‘Why are we still discharging to the street?’ asked Cornes. In 2012 a report published by Homeless Link and St Mungo’s suggested that up to 70 per cent of patients who were homeless were being discharged to the street. In response, the Department of Health and Social Care had released a £10m cash boost to improve hospital discharge arrangements, which had funded 52 specialist homeless hospital discharge (HHD) schemes across England. King’s College had been commissioned to evaluate the schemes over three years, with the aim of showing how to deliver safe transfers of care.

The evaluation showed that homeless people were not being treated the same as others in hospital – for example homeless older people were not being given the same delayed discharge as a patient from a stable background waiting for a care home, to make sure there was somewhere they could go. The intermediate care that had been shown to give ‘enormous benefits’ was in very short supply, even though it was shown to be ‘far more cost effective’ in schemes that had it than schemes that didn’t.

Arranging help on the day of discharge could be invaluable in sorting essential logistics – transporting belongings, registering at the drug service to collect methadone, finding a tenancy that was safe and secure with some heating and basic food ready for arrival, and making sure the person was not alone if they were still feeling unwell.

Motivation to drink

When thinking about longer-term support, it was helpful to know more about motivation said Mick McManus of Barking and Dagenham, who introduced a survey on street drinking in East London. ‘What was their background, what motivated them to drink? Answers to these questions would help to mould our integrated service,’ he said.

Dr Allan Tyler of LSBU explained how their 12-month programme – a collaboration between Westminster Drug Project and LSBU, funded by the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham – combined research and outreach to understand patterns and motives.

The experiences that the team recorded were diverse and showed that not all of the people street drinking were homeless. One important conclusion was that the rich nature of people’s experiences meant that they were not going to create ‘types of street drinkers’.

Among the findings were that many wanted to find a way out of their drinking behaviour, but couldn’t find a path. Others felt stigmatised as ‘weak’ or were excluded from programmes because of a violent past and time in prison. One participant, when asked about giving up alcohol said, ‘Why would I do that? To be the healthiest homeless person in Britain?’

The human touch

Throughout the conference academics shared their findings, but they were illuminated throughout by the contributions of people with lived experience – more relevant than ever representing a population considered ‘hidden’.

‘Your past is not a life sentence,’ said Kevin Dooley. ‘Human beings are capable of change and I’ve lived on second chances all my life… These people are valid and have a voice. These are the ones we need to help us move forward. We can go further and dig deeper – people with experience can contribute to the research and the analysis.’

Lucy Holmes, research manager at St Mungo’s also issued a challenge to researchers – to make their work accessible and easy to absorb.

‘We’re not that interested in methodology – we want stuff that helps us do our job,’ she said, and this could be aided with checklists and toolkits, such as the recent kit on naloxone. Through a lively presentation she urged researchers to get in contact with St Mungo’s, to work together.

‘We do a lot of lobbying, influencing work,’ she said. ‘We sit on project groups, talk to commissioners every day, and we want our messages to be research led. If you want to have real-world impact, talk to us. We talk to the public a lot.’

‘Your research today must reach the coalface,’ agreed Dooley, before chair Tony Moss gave his final thoughts. ‘It’s a relationship between complexity and compassion,’ he said. ‘The more you engage, the more complicated it becomes – but that’s important, because otherwise research is technically inaccurate. Good quality research can start to unpick complications.

‘The sooner you realise a person isn’t in a situation because of the decision they made, the more compassionate you become,’ he added. ‘A whole lot of things in life are out of your control.’

Addressing complexity: homelessness and addiction was organised by the Centre for Addictive Behaviours Research and the London Drug & Alcohol Policy Forum, and held at The Guildhall, London.

The new standards, which come into force in April, include a list of unacceptable content that includes licensed characters from films or TV, certain types of animated characters such as cartoon animals, references to youth culture, and use of sportspeople and celebrities ‘likely to be of particular appeal to children’.

The new standards, which come into force in April, include a list of unacceptable content that includes licensed characters from films or TV, certain types of animated characters such as cartoon animals, references to youth culture, and use of sportspeople and celebrities ‘likely to be of particular appeal to children’.

The figures are based on a measure where alcohol-related diseases, conditions or injuries were the primary reason for admission – using the broader measure of looking at ‘a range of other conditions that could be caused by alcohol’, the numbers rise to 1.2m.

The figures are based on a measure where alcohol-related diseases, conditions or injuries were the primary reason for admission – using the broader measure of looking at ‘a range of other conditions that could be caused by alcohol’, the numbers rise to 1.2m. There are now around 2,000 operative mobile lines compared to 720 in 2017-18, says NCA’s latest

There are now around 2,000 operative mobile lines compared to 720 in 2017-18, says NCA’s latest

The guidance states that pharmacotherapy and behavioural support – which covers most drug and alcohol treatment – can be regarded as primary medical services. ‘It is important to note that some services provided in the community will be “equivalent” to primary medical services and so do not attract a charge for any overseas visitor,’ says the updated document. ‘Examples are services provided by school nurses and health visitors and many drug and alcohol treatment services.’ Previous versions had been unclear on which services were considered equivalent. Inpatient care, however – which includes residential rehab – is not considered a primary medical service and will therefore not be available without charge.

The guidance states that pharmacotherapy and behavioural support – which covers most drug and alcohol treatment – can be regarded as primary medical services. ‘It is important to note that some services provided in the community will be “equivalent” to primary medical services and so do not attract a charge for any overseas visitor,’ says the updated document. ‘Examples are services provided by school nurses and health visitors and many drug and alcohol treatment services.’ Previous versions had been unclear on which services were considered equivalent. Inpatient care, however – which includes residential rehab – is not considered a primary medical service and will therefore not be available without charge.

Drugs searches account for 60 per cent of stop and searches, says the document, although in some areas the figure is far higher – more than 80 per cent of searches by Merseyside Police in 2016-17 were for drugs. In 2010-11 black people were six times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people (DDN, September 2013, page 4), and while this rate has now increased still further, black people use fewer drugs than white people, the report states. In 2016-17 every police force in England and Wales stopped and searched black people at a higher rate than white people.

Drugs searches account for 60 per cent of stop and searches, says the document, although in some areas the figure is far higher – more than 80 per cent of searches by Merseyside Police in 2016-17 were for drugs. In 2010-11 black people were six times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people (DDN, September 2013, page 4), and while this rate has now increased still further, black people use fewer drugs than white people, the report states. In 2016-17 every police force in England and Wales stopped and searched black people at a higher rate than white people. There continues to be ‘significant’ numbers of deaths where illicit drug use has played a role, says the report. These include ‘accidental or deliberate overdoses, suicides precipitated by drug-related mood changes or in response to drug-related debts and bullying, and heart attacks and respiratory failure in apparently fit individuals’.

There continues to be ‘significant’ numbers of deaths where illicit drug use has played a role, says the report. These include ‘accidental or deliberate overdoses, suicides precipitated by drug-related mood changes or in response to drug-related debts and bullying, and heart attacks and respiratory failure in apparently fit individuals’.