Thirty years after Michael Linnell’s first graphic harm reduction campaigns burst onto the scene he recalls the outrage – and the results – that spurred him on

In March 1985 I answered an advert in The Guardian. A small drugs charity called Lifeline was looking for an artist, and they gave the job to me. Over the next 30 years I created a range of internationally acclaimed, and at times notorious, drug campaigns for the most marginalised and stigmatised sections of society.

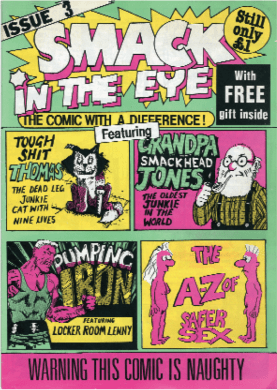

In the mid-1980s, information aimed at drug users consisted of primary prevention campaigns of the ‘drugs are bad’ ilk and a handful of advice leaflets. The emergence of HIV (then called HTLV III) required a new public health response. Tossed like a harm reduction hand grenade into the primary prevention trenches came the rudest drug campaign anyone had ever seen.

In the mid-1980s, information aimed at drug users consisted of primary prevention campaigns of the ‘drugs are bad’ ilk and a handful of advice leaflets. The emergence of HIV (then called HTLV III) required a new public health response. Tossed like a harm reduction hand grenade into the primary prevention trenches came the rudest drug campaign anyone had ever seen.

Smack in the Eye was based on speaking to drug users (a novelty back then) and asking them what they wanted, found funny and were likely to read, rather than what was least likely to cause offence. It had quite an impact. It had been banned by the probation service, reviewed by The Times Educational Supplement and had featured on BBC 1 before the 500 pilot copies of the comic were even distributed. By the time we had been interviewed by the director of public prosecutions (twice), it had been discussed in the House of Lords and commended by the WHO. It was called ‘grossly offensive and pornographic’ and accused of just about every ‘ism’ and ‘obia’ around at the time.

Not only did it contain explicit information on safer drug use and safer sex, it critiqued many aspects of the drugs field – from some of the more pretentious extremes of therapy to mass methadone prescribing. We even highlighted one of the little known but most dreadful consequences of heroin addiction – the delusion that you can write poetry when you give up!

We had expected to be attacked by the press, but surprisingly this came many years later (the Daily Mail dubbed us a ‘threat to the youth of Britain’). It was our fellow professionals who both asked the police to arrest us (nobody was really sure which laws we were breaking but were sure we must be doing something illegal) and occasionally wrote to us complaining. However, these complaints were far outnumbered by the ‘fan mail’ we started to get from drug users.

We had expected to be attacked by the press, but surprisingly this came many years later (the Daily Mail dubbed us a ‘threat to the youth of Britain’). It was our fellow professionals who both asked the police to arrest us (nobody was really sure which laws we were breaking but were sure we must be doing something illegal) and occasionally wrote to us complaining. However, these complaints were far outnumbered by the ‘fan mail’ we started to get from drug users.

By 1990 the ‘acid house’ (rave) scene was flourishing among a group of young people using LSD, amphetamine and ecstasy to get off their trumpet and dance all night to electronic music. We recognised that there was an urgent, unmet need for accurate harm reduction advice for this group and Peanut Pete was designed to change the image of drug services that were perceived to be ‘just for junkies’.

The leaflets were originally distributed at record shops and hairdressers in Manchester. They became an instant success with drug users, so we started to sell them nationally to other services and they sold in their millions, funding our work and allowing us to keep our editorial independence. They also attracted considerable national press interest and we were even (briefly) in the government’s good books when in 1992 the Peanut Pete campaign was described by the European Parliament as ‘by far the best in Europe’ and chosen to represent the UK at the “European Drug Prevention Week” conference.

One of the first people in Britain to die from ecstasy use was a young girl in a nightclub in a Manchester, which was at the time christened ‘Madchester’ by the press. Nobody really knew why the handful of tragic deaths had occurred until we heard that a toxicologist, Dr John Henry, thought the deaths were due to overheating. We managed to get hold of his (at the time unpublished) research and produced Too Damn Hot – a leaflet containing the first ever advice to ecstasy users about heatstroke.

One of the first people in Britain to die from ecstasy use was a young girl in a nightclub in a Manchester, which was at the time christened ‘Madchester’ by the press. Nobody really knew why the handful of tragic deaths had occurred until we heard that a toxicologist, Dr John Henry, thought the deaths were due to overheating. We managed to get hold of his (at the time unpublished) research and produced Too Damn Hot – a leaflet containing the first ever advice to ecstasy users about heatstroke.

In the early 1990s, we had leaflets distributed by drug workers and volunteers who worked in nightclubs (such as The Hacienda) and at “raves”. This led to a campaign of harm reduction information, policy and training around nightclub drug use we called Safer Dancing. It was hugely influential, despite a serious lack of funds, and became the blueprint for the many initiatives that sprang up, both in the UK and internationally.

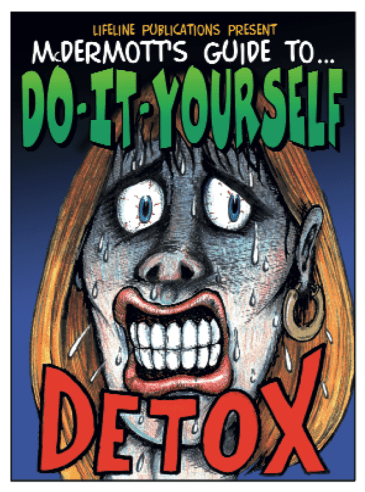

All the publications in the archive were aimed at specific populations of drug users as diverse as children groomed by paedophiles to professional footballers (commissioned by the PFA). They were all based on extensive research with these target populations and we used their expertise. Although there is a long tradition of drug users writing about drugs going back to Thomas De Quincey, it still raised a few eyebrows when in the early 1990s we commissioned a drug user to write about drugs. McDermott’s Guides were designed to be credible and entertaining enough for experienced users to want to pick them up and read them.

However, it was often the pictures that got us into more trouble than the words. An example of this is On the Beat, a booklet based on research with female street sex workers. The ‘sexy’ and ‘glamorous’ images of the women caused some controversy, but that is the way the women we spoke to wanted to be represented, so that is how I drew them.

However, it was often the pictures that got us into more trouble than the words. An example of this is On the Beat, a booklet based on research with female street sex workers. The ‘sexy’ and ‘glamorous’ images of the women caused some controversy, but that is the way the women we spoke to wanted to be represented, so that is how I drew them.

As the new millennium dawned I was managing a research and communications project on homeless populations of injectors. The project had initially been going well and had led to an overdose leaflet, involving police and ambulance services in a joint overdose protocol. The police would now only be called if there was a death or an under-16 involved.

It was when we tried to do something about this unhygienic places where the homeless population were injecting that the project ran into a bit of trouble. We produced an injection box designed as a ‘safe space’ and filled this with all the injection equipment needed for a day – an initiative that led to us being threatened with arrest under section 9a of the Misuse of Drugs Act.

By the end of the project we were under siege, and still under threat of arrest when the Home Affairs Select Committee (HASC) report came out. The Committee (including future prime minister David Cameron) had visited and taken me to dinner to talk about the work. But when the report came out, our publications were accused of ‘crossing a line’ and promoting drug use. This led to the government trying (illegally) to stop anybody buying them with public money: we were under investigation by the Charity Commission and the National Lottery; we had complaints from Prison Officers Association sent to the Prime Minister’s Office and were under attack by the entire national right wing press. The Daily Mail (bless!) called us ‘groovy right-on activists’.

The box was never put out, but the subsequent furore and media storm created by us refusing to kowtow led to the Misuse of Drugs Act being amended to allow for the wider provision of injection equipment at needle exchanges. We survived the onslaught and had the most financially successful sales year in our history.

The work in the archive was produced for a national drugs charity, through setting up a publications department that survived for nearly 30 years just from sales of the publications. That we did this by producing such uncompromising and challenging works is (I think) quite remarkable.

Although many of the publications in the archive rely on the use of humour, I always took the work seriously. I never assumed that information alone would lead to behaviour change and never attempted to tell people that they shouldn’t use drugs, as I never believed this would prevent anybody from using them. The work was first and foremost an attempt to communicate with the target audience of drug users and to show them as people, with all the strengths and weaknesses that make us all human.

Enjoy, but be warned – many of the publications in the archive are still as gloriously rude, vulgar and likely to offend as when they were first created.

Hot off the press! Biffo the clown’s guide to the PSA is now available in the ‘new work’ section at http://michaellinnell.org.uk